Archaeology is ultimately telling the story of our collective human past. Oftentimes, telling the story of people of means has been relatively easy as they leave documents, physical artifacts, buildings, and stories are preserved about them.

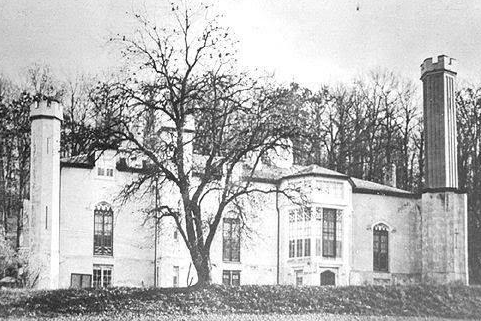

For the people who built and lived on Glen Ellen Estate on what is now Loch Raven Reservoir land in the 1800’s, this is just the case. The Gilmors were people of financial means who had an impact on how Baltimore developed. Robert Gilmor Sr., who immigrated from Scotland in 1767, directed the building of Baltimore’s Washington Monument. He was also reportedly the first American to fly our new national flag on his sailing vessel, a brig named Ann, in the Caribbean. In 1799, the Robert Gilmor and Sons company was the largest East India importing trader of the day.

Forgotten were the other people who lived and worked at Glen Ellen, enslaved people and indentured workers.

Less is known about them because documents are much more sparse. The same Robert Gilmor Sr. who owned land in Baltimore also owned people. We know this from a runaway enslaved person advertisement he placed in a newspaper. Ned, a 25-year-old man enslaved by Robert Gilmor Sr., had run away and was described in the 1786 newspaper advertisement.

Gilmor’s son and grandson not only inherited his wealth but, also, all the items that Robert Gilmor Sr. had lawfully owned. His son, William Gilmor, and his grandson, Robert Gilmor Jr., (who built Glen Ellen Castle) also owned people. We know this from the 1840 census.

The 1840 Census is hard to read therefore, we have enlarged the list below.

The names of the enslaved people were not included on the census list; however, we know the name of one of the enslaved people who were counted in the census. This is documented in a runaway enslaved person advertisement.

Levi Cosley was 35 years old in October 1840 when he attempted to escape from his enslavers. The warden of the Baltimore City and County Jail placed this ad in the newspaper to find his owner.

Unfortunately, his enslaver came too late. The next mention of Levi Cosley in the Maryland State Archives is on January 21, 1841, when a member of the Gilmor family came to the jail to retrieve his body. The cause of death is not recorded.

In December 1846. a property assessment was conducted for the Robert Gilmor Jr. The list contains, among mills and livestock, a tally of enslaved persons separated by age and sex.

As on the census, no names of the enslaved persons are listed. And once again, we know the name of one of the enslaved persons from a runaway enslaved person advertisement. Stephen was 21 years old when he attempted to make his way to freedom. There is no further mention of him in the archives, so he may have been successful in his attempt.

In the 1850 census, four laborers from Ireland are listed as living with the family on the Glen Ellen Estate.

In addition to the runaway enslaved person advertisements, there are also three certificates of freedom found in the Maryland State Archives concerning people enslaved by the Gilmors. A Certificate of Freedom is a legal document that was issued to African Americans who were required to record proof of their freedom in the county court. If the person had been previously manumitted (set freed from slavery) by an act of the slaveholder, the court clerk or register of wills would look up the manumitting document before issuing a certificate of freedom.

“Negro” Sarah is freed by William Gilmor in 1832. She is described as light skinned with a small mole on her chin. Robert Gilmor Jr. is listed as the witness on the document.

In 1837, Ann Barnes is freed by Robert Gilmor Jr. She is described as light skinned and straight reddish colored hair.

In 1838, Reuben Brown, described as being raised in Baltimore County, is freed. The reason Reuben is freed is probably evident from the physical description of him: “right hand much swollen and disfigured”.

Interestingly, Brown is a family name common among enslaved persons at Hampton Plantation, known today as Hampton National Historical Site, which lies next door to the Glen Ellen estate. In fact, Robert Gilmor Jr. had purchased the property from one of the Ridgely family daughters, Priscilla Ridgely White on June 18, 1832. He bought 1,037 acres from her at $18 an acre.

Hopefully, we will be able to learn more about the history of all the people who lived in Maryland. As more research files are uploaded to the internet, a dedicated researcher will be able to find more information. As the Hampton webpage states: “Primary sources, public records, research documents, oral histories and site visits have provided important discoveries in this ongoing work.”

If anyone is interested in conducting or helping out on research for the NHSM Archaeology Club, please contact us. We welcome people of all levels of experience.

FYI:

Hampton National Historic Site and Goucher College (which sits on former Ridgely family land) have conducted much research into the enslaved persons who lived there. Visit Slavery at Hampton – Hampton National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service) (nps.gov) and The Hallowed Ground Project | Goucher College for more information on their research.